by Giulio Volpe, Avvocato dell’arte, con studio in Bologna, fornisce consulenza e assistenza legale agli operatori del mercato dell’arte, a collezionisti privati e società.

È passato un anno da quando, incaricato dalla Federazione Italiana Mercanti d’Arte (Presidente Fabrizio Pedrazzini) per il IV Convegno FIMA (a cura di Carlo Teardo), nel contesto piacevole e congeniale di Modenantiquaria (coordinata dall’ottimo Pietro Cantore) tenevo una relazione sulla disciplina italiana in materia di circolazione dei beni culturali, anche nel raffronto con altri ordinamenti europei.

Il giorno successivo procedevo alla presentazione delle proposte scaturite da alcuni tavoli tematici composti dagli stessi antiquari, alla presenza del Sottosegretario di Stato Vittorio Sgarbi e di alcuni parlamentari che di lì a poco le avrebbero commentate, nonché di Umberto Allemandi in qualità di straordinario moderatore.

Il documento conclusivo, teso all’armonizzazione della disciplina italiana con le principali normative europee, conteneva tra altre le richieste che seguono: il rispetto di tempi certi nei procedimenti amministrativi concernenti circolazione in entrata e uscita di cose di interesse artistico e storico; la redazione di un database o archivio unico delle opere “vincolate”; la previsione di una decisione espressa obbligatoria a fronte di ricorsi gerarchici amministrativi entro i 90 giorni previsti; un adeguamento della disciplina interna in materia di circolazione delle cose di interesse artistico e storico alle soglie di valore di cui al Regolamento CE 116/2009, mettendo in evidenza che queste sono state perfino elevate o raddoppiate in altri Paesi membri.

Se infatti da un lato dobbiamo guardare con profondo rispetto alla tradizione italiana di tutela del patrimonio storico artistico, che rimanda a quella rarissima congiunzione astrale che avvinse intorno a Pio VII Chiaramonti figure di altissimo profilo, quali furono il giurista erudito Carlo Fea o l’Ispettore delle Belle Arti Antonio Canova (in veste di amministratore tecnico, come lo era stato Raffaello tre secoli prima), dobbiamo considerare che il nostro territorio in epoca preunitaria era afflitto da un’incessante emorragia di opere d’arte e come il sistema giuridico amministrativo di controllo e di sanzione, ancora in fase embrionale, rimanesse spesso sulla carta.

È a tutta evidenza assurdo, per fare un esempio limitato ai dipinti, che oggi in Francia come in Germania la soglia di valore rilevante ai fini della tutela in sede di esportazione sia di 300.000 euro, nel Regno Unito di 180.000, mentre in Italia quasi sarcasticamente tale soglia, raggiunta a fatica e da buoni ultimi, si attesta sui 13.500 euro.

È altrettanto disarmante pensare che se in Francia l’Amministrazione può fermare l’esportazione di un bene, lo possa fare per un massimo di trenta mesi, entro i quali dovrà raccogliere i fondi utili ad acquistarlo.

Di più, alcuni Paesi membri (ancora la Francia su tutti) stabiliscono con chiarezza che entro un dato termine, in mancanza di acquisto (a prezzo di mercato), il certificato di esportazione non potrà essere negato. Rassicurante, ancora una volta in Francia, la presenza di esponenti della giurisdizione amministrativa (la presenza di un Consigliere di Stato) nelle Commissioni incaricate di decidere sulle richieste di esportazione e sul riconoscimento dei tesori nazionali, a garantirne la terzietà e a scongiurare l’appiattimento su posizioni preconcette.

PER LEGGERE L’INTERA PUBBLICAZIONE CLICCA QUI

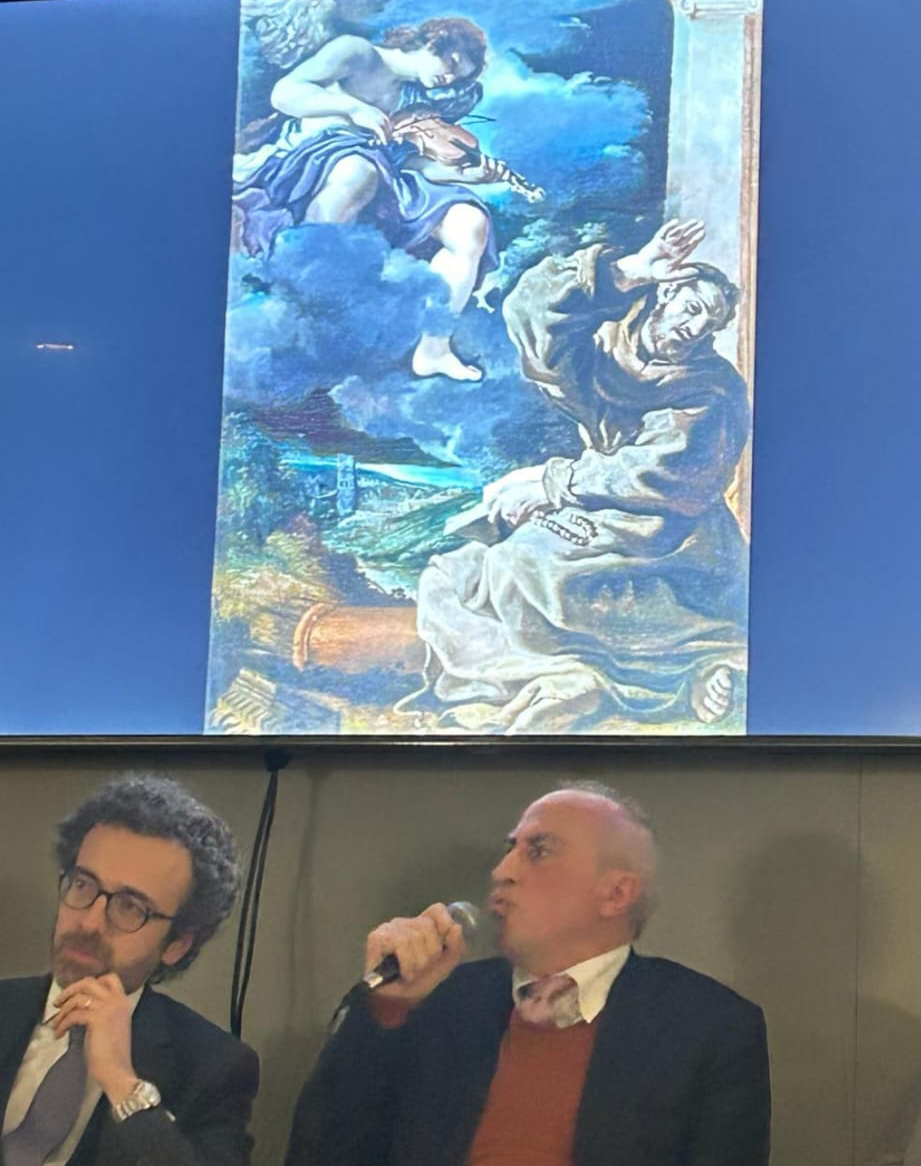

FIMA conference in Modenantiquaria 2023, the lawyer Giulio Volpe is third from the left. The

first from the right is the former ex Undersecretary of the Ministry of Culture Vittorio Sgarbi

A year has passed since, commissioned by the Italian Federation of Art Dealers (President Fabrizio Pedrazzini) for the IV FIMA Conference (curated by Carlo Teardo), in the pleasant and congenial context of Modenantiquaria (coordinated by the excellent Pietro Cantore) I held a report on Italian regulations regarding the circulation of cultural goods, also in comparison with other European systems.

The following day I proceeded to present the proposals resulting from some thematic tables made up of the same antique dealers, in the presence of the Undersecretary of State Vittorio Sgarbi and some parliamentarians who would shortly comment on them, as well as Umberto Allemandi as extraordinary moderator.

The final document, aimed at harmonizing Italian regulations with the main European regulations, contained among others the following requests: respect for certain times in administrative procedures concerning the movement in and out of things of artistic and historical interest; the preparation of a single database or archive of “restricted” works; the provision of a mandatory express decision in response to administrative hierarchical appeals within the foreseen 90 days; an adaptation of the internal regulations regarding the circulation of things of artistic and historical interest to the value thresholds referred to in EC Regulation 116/2009, highlighting that these have even been increased or doubled in other member countries.

In fact, if on the one hand we must look with profound respect at the Italian tradition of protection of the historical and artistic heritage, which refers to that very rare astral conjunction which brought together figures of the highest profile around Pius VII Chiaramonti, such as the erudite jurist Carlo Fea or the Inspector of the Fine Arts Antonio Canova (in the capacity of technical administrator, as Raphael had been three centuries earlier), we must consider that our territory in the pre-unification era was afflicted by an incessant hemorrhage of works of art and how the administrative legal system of control and sanctions, still in the embryonic phase, often remained on paper.

It is clearly absurd, to give an example limited to paintings, that today in France as in Germany the relevant value threshold for the purposes of export protection is 300,000 euros, in the United Kingdom it is 180,000, while in Italy almost sarcastically this threshold, reached with difficulty and with good results, stands at 13,500 euros.

It is equally disarming to think that if in France the Administration can stop the export of a good, it can do so for a maximum of thirty months, within which it will have to raise the funds needed to purchase it.

Furthermore, some member countries (France above all) clearly establish that within a given deadline, in the absence of purchase (at market price), the export certificate cannot be denied.

Reassuring, once again in France, is the presence of representatives of the administrative jurisdiction (the presence of a State Councillor) in the Commissions responsible for deciding on export requests and the recognition of national treasures, to guarantee their impartiality and to avoid the leveling of preconceived positions.

Nor is there a lack, outside Italy, of cases of formidable private donations in support of the cultural heritage of one’s own country.

TO READ THE COMPLETE ARTICLE CLICK HERE